Graveyard Shift is a vocational night shift simulation. Stocking shelves, sweeping spills, serving ghosts and playing games on your phone will occupy your time in your little convenience store world.

The primary goals for this project were:

- to create a modular set of systems that can be expanded upon and support rapid implementation and iteration.

- to develop a full and flexible play experience that accurately represents a quirky take on night shift employment.

* * * * *

Solo Work - 12 Weeks - School Project (Year 4)

Graveyard Shift

This was by far my most favorite solo project to-date. I got to add a lot of fun little baubles onto what was setting out to be a larger-scope game, and I have the hard work I did in the beginning to thank. Without such a strong pipeline and foresight into my eventual design trajectory, this game could have turned out a lot messier than it did.

I wish, as most developers do, that I had more time to work on it. There were a few things I half-implemented, such as hot dog condiments, temperature changes on foodstuffs, poltergeists, and more stocking items that I just didn't get through to the end. I don't think the project suffers from not having these things, but they would have enriched the experience a whole lot more.

This game really proved the power of planning to me. In previous solo games, I had the start of an idea of what pipeline and technical design can achieve, but this game was so far beyond those. I will be using a similar planning methodology in all of my future projects, and the front-loading of work in the beginning saves a lot of headache and heartache in the end.

Synopsis

Week 2 - Fantasy

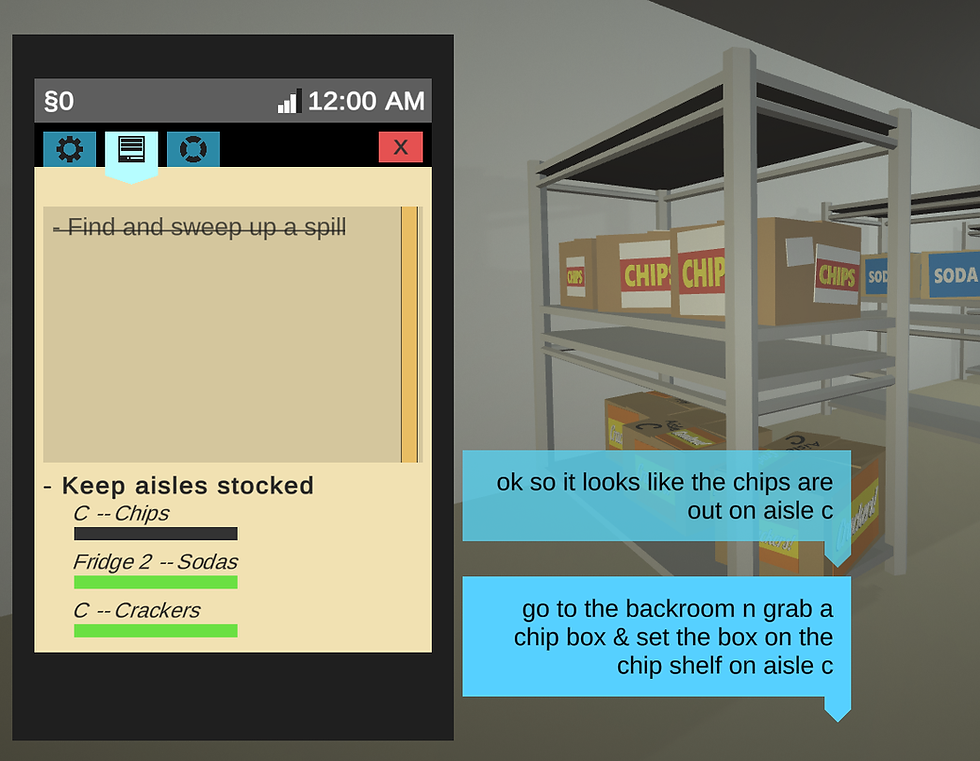

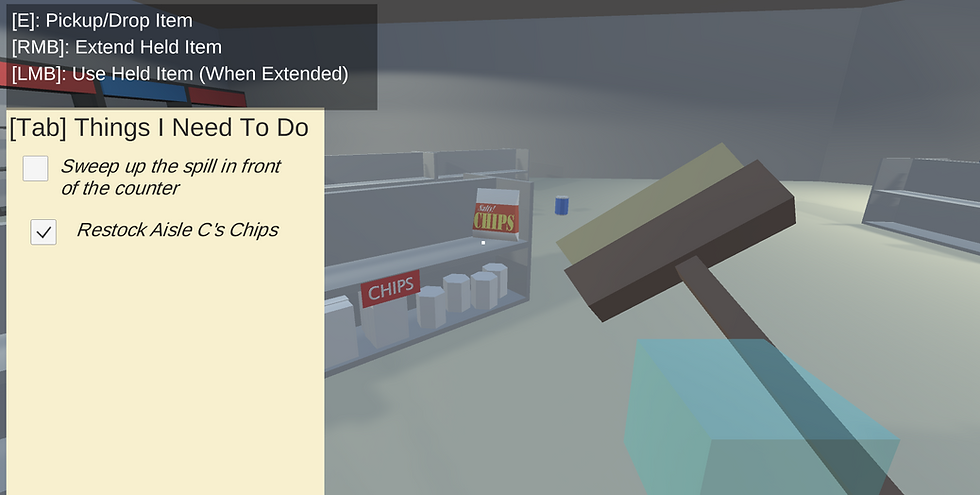

The core of the night shift convenience store worker's job can be distilled into a few simple actions: walking, picking things up, putting things down, and interacting with other things with the things you've picked up. These four things are where I started, taking the most archetypical objects in a convenience store (broom, junk food, shelves) and developing a code base that works with all of these things modularly -- I knew I would be adding more items in the future, and writing similar behaviors for each to be able to pick things up sounds like a massive waste of time.

The main feedback from the space in this version, the checklist, is a means to quantify the player's actions in some summary form. I knew I was going to be tracking player activity in some way down the line, so getting the basic scripting in for that helped structure supplementary modules around that concept early, before I'd need to refactor it.

Week 4 - Identity of Self

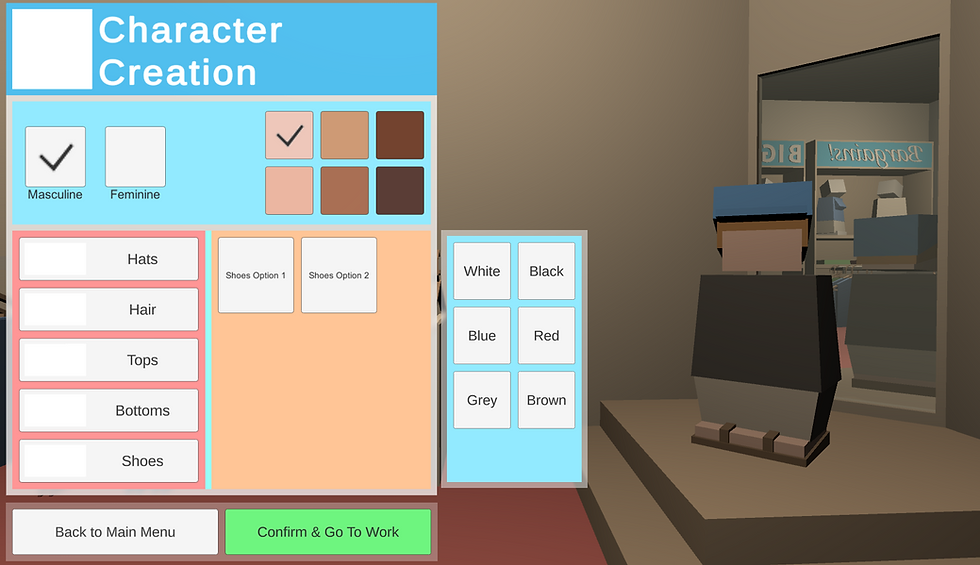

I made a basic character creator for this game, mainly because my goal for the project is to make a player feel like they exist in this world, rather than looking through a glass screen. As a medium of transferring a lookalike image of oneself or of exploring alternative means of self-expression, I wanted this character creator to be fun and quick to use. It's very much one of those things that can be scrapped completely and not hinder the core gameplay, but it served as a satisfying challenge for me and a wonderful initial source of engagement and investment for my players.

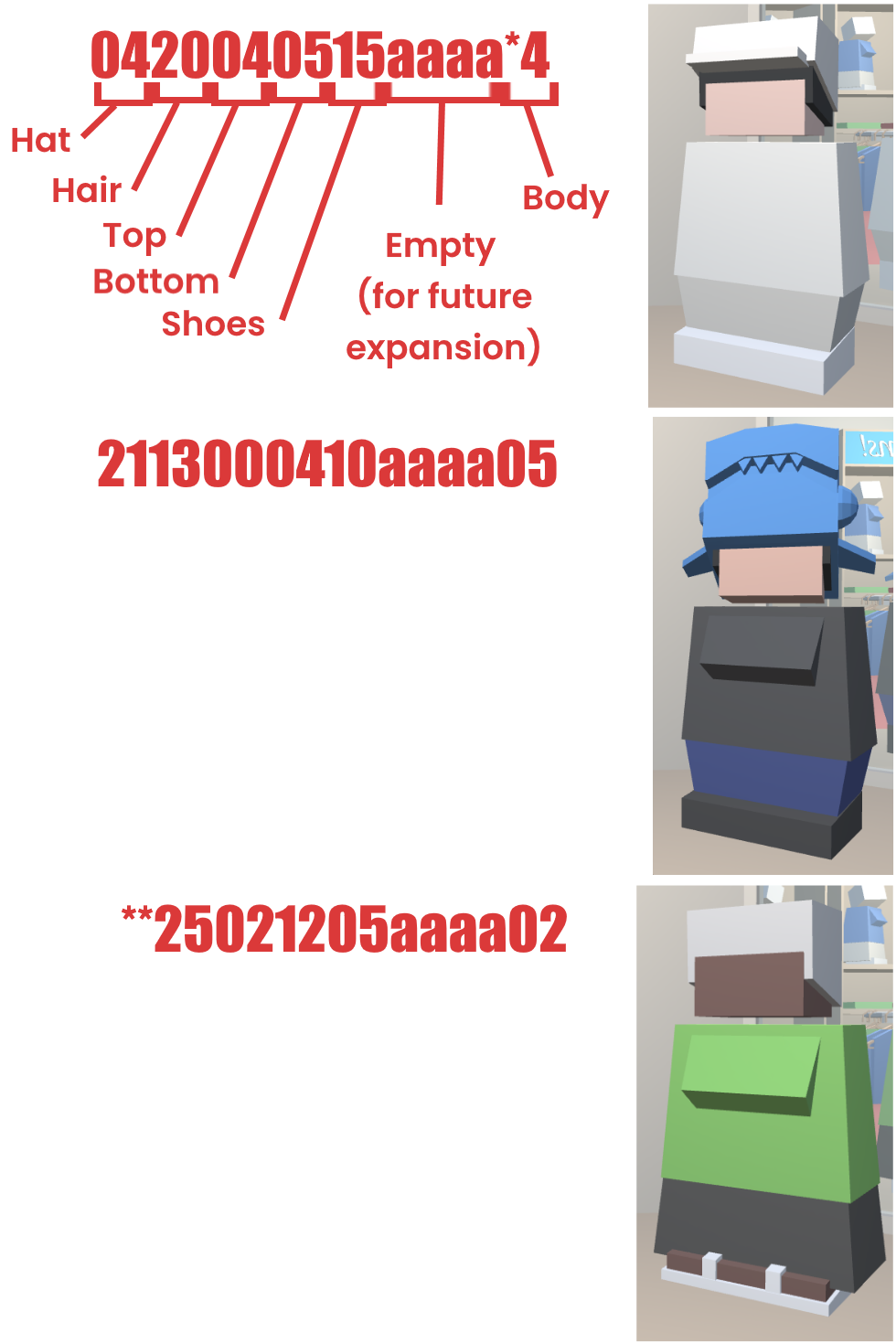

The most important technical concern for me was to develop an incredibly easy-to-use pipeline for asset implementation, and the character creator is a prime example. The player's decisions are recorded in a 16-character string, each character representing the shape or color of every section of customization. Every possible combination of assets can be expressed by this string, which offloads a lot of data storage (16 characters rather than the exact models), and allows for an incredibly easy expansion of player choices.

A resource directory structure is read and enumerated, each asset in a particular folder spawning a button associated with its position in that folder. When the button is pressed, it calls for the asset to be loaded and displayed to the character, changing the string in the process. A lot of other back-end stuff allows for rapid implementation (the shark hat, seen in the second string example, took 15 minutes from initial concept to full working implementation, including the modelling process).

I'm designing this game not only for the user, but also for the designer making it (me). Asset implementation can take a while to hook up to specific systems, so designing a structure that allows for a powerful "drag-and-drop and it's done" system was really helpful in developing this game quickly and efficiently.

The Timeline

Week 5 - Alpha

Ghosts! Night shift workers are also responsible for helping nocturnal (and sometimes eccentric) customers, and this game was crying out for ghosts to populate a player's "graveyard shift". The ghosts are quite simple in design. They queue up, as for an item, pay and leave. Their role is to break the monotony of nighttime shopkeeping, and I think they do that well. Similarly to the character creator, they are placed into the world from a directory of preset personalities. This allows for rapid expansion and iteration of the pool of ghosts, rather than writing very specific ghosts for very specific points in the experience.

In this version, I also added time and money. The former is a system for containing the gameplay experience into a finite space, one which can expand and contract dynamically with the change of one variable -- since ghosts and other interactions show up based on the in-game time, changing the scale to real time doesn't break the experience, it just shortens or expands the downtime between events.

Week 10 - Beta

The big hurdle for this milestone was structure. I had a few good independent pieces, but I needed to find a way to connect them into a sequence of events in the player's head. My solution: Jeff.

Jeff is an omniscient and omnipresent dudebro friend who guides the player through his employment routine after the player agrees to cover the shift for him. I had no idea how to make a dialogue system when starting on Jeff, and I'm pretty sure I did not do it the "right" way. However, I developed a system inspired by CSV that encodes not only line breaks, but message breaks, flags for whether something needs a response, and flags for what responses should be displayed. I can also call a specific response with an interaction with the world, rather than a dialogue response. The input file is just text, and it looks something like this:

Hello, this is the first message;Every message is ended by a semicolon to tell the script when it ends;Every message that asks for a player response ends with asterisk. Would you like to know more?*;>Yes;>No;

The drawbacks with this system are plenty, such as a lack of the ability to use ";", "*" and ">". Responses also don't have any direct link to their corresponding next text file, so that had to be done in script. However, this worked well for what I needed, and it made iteration of the tutorial much faster and cleaner.

The tutorial itself is delivered primarily through text, but there is very little downtime for the player and it's designed such that the key information stays on-screen until the player does the very simple task.

Week 12 - Release Candidate

The last two weeks were my favorite part of the project, mainly because they were so low-stress. I effectively set up a powerful pipeline of tools to rapidly iterate on my existing features, and this allowed me to breeze through a polish phase after Beta. Nothing of note came up in playtesting, so I could spend all my time giving things a facelift. This primarily came in the form of reworking and adding more audio feedback, quality of life changes like more confirmations of destructive action, a Simon-style minigame, etc.

It's quite euphoric to breeze through the finish line, especially with the expectations that the end of a project is its busiest.